This Week in Native American News (1/11/19): commemorating and healing history , purchasing mines, and analyzing treaties

January 11, 2019

250th Anniversary Mission of San Diego’s First Church: Healing ‘Great Pain’

Attendees enter California’s first mission before prayer service commemorating the start of its 250th anniversary year. Photo by Chris Stone

The 22nd successor of Saint Junipero Serra as pastor of Mission San Diego de Alcalá, California’s first church, opened what he called a memorable year in its history Thursday by seeking to heal wounds of its early years.

Launching a year of 250th anniversary events, the Rev. Peter Escalante told an overflow audience that the California missions brought “great pain to the Native American people. And that pain is hidden within these walls.”

He noted the jubilee year in which two interwoven traditions blend at Mission San Diego — the Spanish Franciscan way and the American Indian spirituality, “which practices respect for the Earth and the divine spirit that fills it.”

Read the Full Story Here

In Similar News…

Innovative Park Programs Help Tell Native American Stories to a New Generation

Designated by Teddy Roosevelt in 1906, Arizona’s Montezuma Castle National Monument became one of the first national monuments, preserving cliff dwellings in North America and showcasing the Sinagua culture’s ingenious use of the desert landscape to prosper for generations.

For many students, a visit to a national park is a way to learn more about their culture and heritage. Saguaro National Park participated in Hands on the Land, a program focused on bringing Native American students to their local national park. During the 2017-2018 school year, more than 100 students from local bicultural schools for Tohono O’odham youth took part in the program.

Navajo Nation considers taking over large Arizona coal mine and power plant

Charlotte Begay, 64, of Shonto, Ariz., breaks up coal with a pickaxe at the public loadout facility at the Kayenta Mine on Feb. 4, 2017. The mine's sole customer is the Navajo Generating Station, a coal-fired power plant near Page, Ariz. If the power plant shuts down it not only would impact plant workers, but coal miners as well. Mark Henle/The Republic

The Navajo Nation is considering taking over the Kayenta Mine in addition to the coal plant near Page that is scheduled to close this year, speaker LoRenzo Bates said Monday.

The revelation shows an increased willingness by the tribe to take risks to keep the coal facilities running. Any deal to acquire the mine and the largest coal plant in the West will involve not only the price, but also the clean-up liability.

Nonetheless, Bates said the tribe must consider all options because the facilities are so critical to the tribal economy.

Bates also said that the Navajo Nation has years worth of coal in the ground, which someday could be used for other purposes such as making liquid fuels. Shutting down the operations could foreclose any opportunities to sell the coal for those uses.

The tribe announced in November it was considering taking over the troubled Navajo Generating Station, and Bates said the tribe for months has also been exploring taking over the mine from Peabody Energy.

Read the Full Story Here

Native American tribe member who killed elk to feed family asks Supreme Court to throw out poaching conviction

The Cloud Peak Wilderness area, located in Bighorn National Forest in Wyoming, is pictured in an undated photo. (Casper Star-Tribune/AP, FILE)

Members of the Crow Tribe hunt elk to feed their families.

The state of Wyoming says they can't kill the animals on federal forest land without a permit.

The Supreme Court will now decide whether an 1868 treaty protects the Native Americans' right to hunt.

During a 2014 hunting expedition, Clayvin Herrera and three other tribal members pursued a small herd of elk as it moved from the Crow Reservation in Montana to the Bighorn National Forest in Wyoming. There the hunting party "shot, quartered and packed" three elk, and carried the meat back to the reservation, dividing it among their families, according to court documents.

Wyoming game officials later tracked down Herrera and charged him with hunting off season and without a license. A state court convicted Herrera, and he was ordered to pay an $8,000 fine and give up hunting privileges for three years.

Herrera said the Second Treaty of Fort Laramie from 1868 -- between the United States and Crow Tribe, before Wyoming became a state -- expressly allows tribal members to legally hunt in unpopulated federal forest lands at any time.

Read the Full Story Here

An Artist Addresses the Field Museum’s Problematic Native American Hall

Installation view of Drawing on Tradition: Kanza Artist Chris Pappan at The Field Museum PHOTO: © JOHN WEINSTEIN, COURTESY OF THE FIELD MUSEUM

Little has changed in the Field Museum’s Native North American Hall’s displays since the 1950s. Faceless mannequins dressed in headdresses and moccasins, beadwork, hide paintings, spearheads, and textiles are all encased behind glass. Complete with midcentury typefaces and muted pastel backdrops, the exhibit gives the impression of being frozen in time.

The case labeled “Indians of the Chicago Region,” for instance, makes no mention that the greater metropolitan area now has the nation’s third largest Native American urban population. This restricted view can be traced back to the museum’s beginning. Native American objects acquired for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition by anthropologist Franz Boas — who believed he was salvaging remains of disappearing cultures — were part of its founding collections.

After six decades of this static display, the tribal nations connected to these objects will finally have a voice in their presentation, emphasizing their place in living culture. In October, the museum announced a three-year renovation of the hall. When it reopens in 2021, it will not just represent a new direction for the Field Museum but will reconsider what natural history museum ethnographic galleries can, and should, be in the 21st century. The challenge is in recognizing the colonialism in their roots while involving indigenous voices that have long been left out.

Read the Full Story Here

Today’s History Lesson

Richard Oakes led Native Americans to occupy Alcatraz in 1969 — his tragic story is finally being told

The 1969 occupation of Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay is one of the most notable acts of political resistance in American Indian history. In Kent Blansett’s latest book, “A Journey to Freedom: Richard Oakes, Alcatraz, and the Red Power Movement,” he captures the action as it happened: “Dressed in blue jeans, a sweater, and a cherished pair of cowboy boots, Richard Oakes made his way to the side of the boat. Looking over at the waves and the island, he turned to the crowd and motioned, ‘Come on. Let’s go. Let’s get it on!’ Within a few seconds, his shirt was off; his large frame disappeared into the chilled November waters, his boots still on as he swam for the land.”

In 1919 Ireland's President became an honorary Native American chieftain in Wisconsin

Gibbons had long been suspicious of Irish nationalist movements and played little or no public role in the Home Rule cause in the 1880s and 1890s, but he had grown to reluctantly support the cause of Irish freedom between 1916 and 1919.

In February 1919, Gibbons unenthusiastically read a resolution calling on the peace conference in Europe to apply “the doctrine of national self-determination” to Ireland. De Valera’s visit to the “Chippewa Reservation” in Wisconsin gave him the opportunity to use Wilson’s language of self-determination against him and shame Americans about their own colonial past.

Why Native American nations declared war on Germany twice

After members of the Blackfeet Nation overwhelmed an Army recruiting office in 1941, those waiting in line cried, "since when has it been necessary for Blackfeet to draw lots to fight?"

Hitler surely didn't realize the fight he was picking.

Japan kicked off their war with the U.S. with a bang — no declaration necessary. Their formal declaration came the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor. One by one, the United States and the Axis countries declared war on one another. But the war between Native American nations in the United States and Germany had never actually been resolved, so they just resolved to continue fighting.

New Alaska Native art installation commemorates cultural history and generations of fishing at Ship Creek

The art installation, at the Anchorage small boat launch, was more than a decade in the making. The piece marks the spot of a traditional Dena’ina fish camp at the mouth of Ship Creek. It is a commemoration of the Native Village of Eklutna and cultural history, and a rare example of outdoor art in the Anchorage area that reflects Alaska Native culture, people involved with the project said.

“It’s a pretty significant thing to have our people accurately represented, in an accurate likeness of what we’re doing,” said Joel Isaak, the Soldotna-based artist who created the sculpture who is himself Dena’ina.

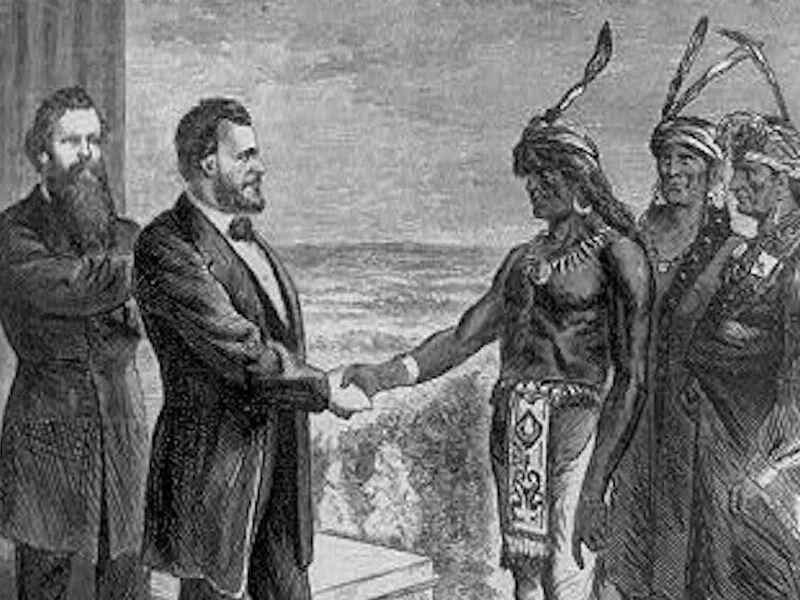

Ulysses Grant’s Failed Attempt to Grant Native Americans Citizenship

The man elected president in 1868—Ulysses S. Grant—was determined to change the way many of his fellow Americans understood citizenship. As he saw it, anyone could become an American, not just people like himself who could trace their ancestry back eight generations to Puritan New England. Grant maintained that the millions of Catholic and Jewish immigrants pouring into the country should be welcomed as American citizens, as should the men, women, and children just set free from slavery during the Civil War. And, at a time when many in the press and public alike called for the extermination of the Indians, he believed every Indian from every tribe should be made a citizen of the United States, too.

It's hard to fit so much news in such a small space.

To read all of this week's news, visit the LIM Magazine.

Sign up to get these emails in your inbox and never miss a week again!