This Week in Native American News (2/9/18): Caring for Children, Doing Mental Math, and Fighting Abuse

February 9, 2018

Navajo Woman Opens Her Home to Thousands of Foster Children

Ronald Joe has been helping Vallis Martinez with her foster kids for the last three years. Joe says, many of Vallis' foster children come back to visit her as adults. Grandparents will stop her in the grocery store and thank her. (Laurel Morales)

Vallis Martinez has had as many as 16 children at one time in her tiny home. She’s also raised three of her own. When the children arrive she said they don’t want to talk. But she shares with them her own story of abuse and they usually open up.

Martinez has lost count of how many foster children she’s cared for on the Navajo Nation. She said it could be as many as 10,000. And the Navajo Department of Family Services wishes there were more like her because the demand for safe foster homes is so high. The tribe places about 2,400 kids a year with relatives or foster parents.

Foster home licensing specialist Elsie Elthie calls Vallis Martinez a superhero. Elthie only has two emergency homes she can turn to on the western side of the reservation. The other homes are in Flagstaff and Phoenix.

Elthie was once a foster kid herself before the time of the federal law. A white foster mom in California cared for her and told her, "I couldn’t love you more if you were my own daughter." Elthie wanted that for other children who’d been abused or neglected.

“We use the concept of ké. Even though they aren’t blood relatives, I’m going to treat them like family. It means, even though it’s the middle of the night, even though I haven’t had anything to eat, I’m going to help them as much as I can.”

Read the Full Story Here

You Might Also be Interested in...

Inside the Native American Foster Care Crisis Tearing Families Apart

A shortage of Native foster families has led to pain, lawsuits, and echoes of a painful history.

Nationwide, American Indian and Alaska Native children are placed into foster care at a rate 2.7 times greater than their proportion in the general population, according to the National Indian Child Welfare Association (NICWA). With a disproportionate number of Native kids removed from their homes each year, the need for Native foster homes is huge—and there aren’t enough to meet the need. That shortage leads to non-Native foster parents taking in kids from tribal communities. Sometimes, those foster parents decide they want to adopt the foster child even though the law is supposed to prevent virtually all such non-Native adoptions.

To understand these disputes, you have to know the painful history behind them. Before the enactment of the 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), the law that governs removal and placements of Native kids, 25 to 35 percent of Native children nationwide were being removed from their families, according to NICWA.

Read the Full Story Here

The Difficulty Math of Being Native American

Purestock/Getty Images

Savannah Maher writes:

My friend and I were raised by different tribes on reservations 3,000 miles apart. As children, though, we internalized the same directive: Find yourself a Native man. Good blood for your babies.

I know how messed up it sounds. But it's about survival.

It's called blood quantum. Lots of Native nations, including my friend's, use it to determine who can and can't enroll as a citizen. But even in tribes like my own that use different enrollment policies, the notion that Indigeneity can be quantified — that it's our "blood" that makes us Native or not — is impossible to avoid.

On the phone, my friend tells me that her current beau checks most of these boxes. They've only been together for two months, but she's done the math. (1/4 + 5/8) ÷ 2 = 7/16 and just like that, their babies will be Indian enough. The hard part is over. All that's left to do is fall in love and stay there.

Here's the thing about blood quantum: it's not real. It has no basis in biology or genetics or any Indigenous tradition I'm aware of. It's a colonial invention designed to breed us out of existence. But it's got all these smart people—traditionalists, university students, Indigenous language revitalists—running around doing mental math, convinced it's our best shot at keeping our cultures alive.

Read the Full Story Here

How a Remote Alaskan Island Tackled Domestic Abuse

Zachary Lamblez, the chief of police and director of public safety. Lamblez, a former US marine, has been a tribal police officer for 16 years. Photograph: Ash Adams for the Guardian

Generations of sustained traumas haunt the Aleut Community of St Paul Island, but shelters, social workers and programs aim to help.

Generations of sustained traumas – slavery, dislocation, oppression – still hurt the Aleut Community of St Paul Island, a federally recognized Indian tribe. This manifests as child abuse, domestic violence, sexual assault and addiction. To fight this, the tribe took matters into its own hands.

The key to social change required one crucial component: financial self-determination.

St Paul now has domestic violence shelters, social workers and culturally relevant programs for healing. It has the buildings, people and authority to meaningfully and quickly assist individuals in crisis. It’s doing things differently: cross-deputizing city police to enforce tribal law; making rape kits available on-island to make the forensic examinations process as speedy as possible, and hopefully, lead to more prosecutions.

Both are firsts in the state of Alaska.

The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 gave St Paul the authority it needed to self-manage federal funds designated for housing, education, healthcare, child welfare, courts, transportation and the environment.

Where before St Paul received about one out of every four dollars meant for it, 70 to 80% of the money now stays on the island, said Baker.

In 1995 the tribe had five employees and ran a bar. Now, it’s bringing in over $10m a year, employs 68 people and pays out nearly $3m in wages. The tribe’s most recent bold move – transferring its healthcare from one regional non-profit to another – freed up $1.5m, money it’s pouring directly into programs to improve quality of life on the island.

The tribe predicts the social problems it’s hoping to get rid of will take generations to overcome, just as they took generations to create. Because the island’s wellness programs are so new, just changing one life, one family, is enough.

Read the Full Story Here

See the 5 Finalists for the National Mall’s First Memorial to Native American Veterans

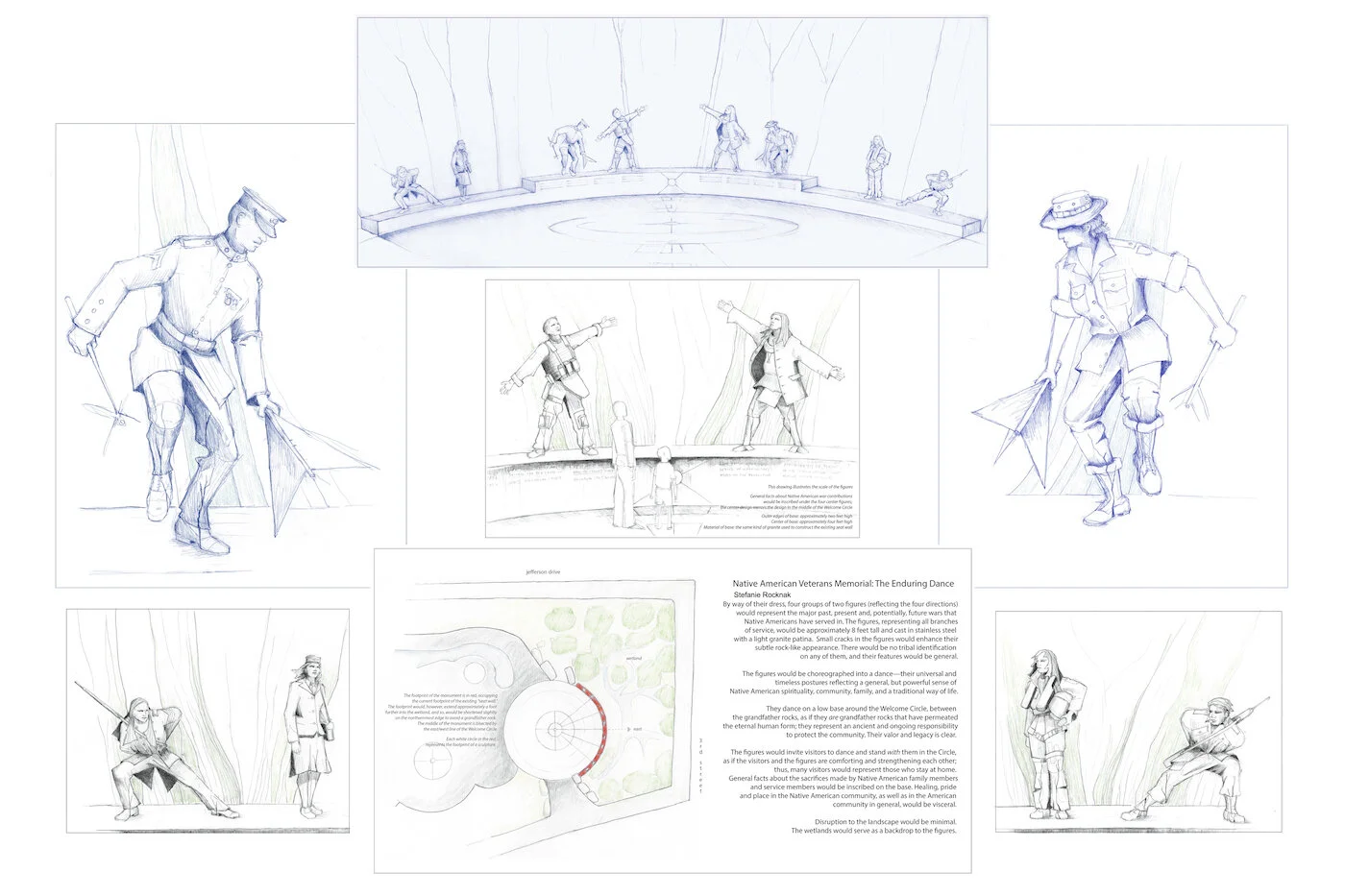

“The Enduring Dance,” design proposal by Stefanie Rocknak

A decades-old plan to honor Native American veterans with a prominent memorial on the National Mall is on its way to becoming a reality. Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) today shared five potential concepts for the permanent monument that will eventually stand on its grounds, designed by artists who responded to an open-to-all, international design competition the museum launched last fall.

A jury of Native and non-Native artists, designers, scholars, and veterans selected the five designs out of 120 submissions from around the world. (The only international finalist is Leroy Transfield, who is Māori.) To help guide that process, NMAI had established an advisory committee, composed of Native veterans and tribal leaders from across the country, which had traveled for nearly two years to speak to different Native communities to seek their feedback on what the memorial should express. The official competition guidelines asked that proposals reflect Native spirituality; honor American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiians; and not include markers of specific tribal identification, among other stipulations.

See the 5 Finalists (at the bottom of the article)

In the Arts...

Etsy Banned Alaska Native Artists from Selling Ivory

A policy intended to deter the illegal trade of ivory and items made with the parts of endangered or threatened animals led the online sales website Etsy to remove such artwork sold by Alaska Native artists, who can legally use ivory in their pieces.

U.S. Sen. Dan Sullivan asked the chief executive officer of Etsy.com to reconsider its policy to allow Alaska Natives to keep selling products made from materials such as walrus tusks or from petrified wooly mammoth remains found in the nation's most remote state.

Nunavik seamstress embellishes tradition

In a sea of sealskin and colourful commander fabric, Winifred Nungak’s booth stands out for its pop of pink, from plush pompoms to dyed fox-fur mittens. Nungak’s work, which she sells through her business Winifred Designs, has made a name for itself through the Inuit Nunangat and beyond.

“Growing up, I think every Inuk woman sews,” she said. “We grew up watching our mothers and grandmothers, so it’s in our DNA—it’s part of our lives.”

Nunagak said she’s proud to be one of a growing number of Inuit seamstresses who are making a name for themselves and re-defining Inuit fashion.

Hand-Beaded Vans Go Viral

Artist Charlene Holy Bear, a member of the Standing Rock Lakota Sioux Tribe, was heading to a pan-tribal festival called the “Gathering of Nations” in Albuquerque, New Mexico when the idea struck her. “I hadn’t had any time to prepare outfits for us but I wanted my 4-year-old son Justus to look really cool," she told Vogue. "He had a new pair of slip-on Vans and I suddenly had an idea, looking at the checkerboard design.” After that, she started hand-beading the shoes to make them look like traditional moccasins. “Once they were beaded they had this sort of urban Indian vibe so I braided my son’s hair, put on those shoes and he was the coolest little guy at the pow wow.” she continued, “People were stopping us to take photos, he made such a splash.”

"Heart Berries," by Terese Marie Mailhot, gets rave review from Sherman Alexie

“I was aware,” Alexie writes, “within maybe three sentences that I was in the presence of a generational talent.” If that weren’t enough, in his blurb, he calls the book — centered on Mailhot’s coming of age on the Seabird Island Indian Reservation in British Columbia and later as a writer — “an Iliad for the indigenous,” invoking Homer’s classic saga.

It's hard to fit so much news in such a small space.

To read all of this week's news, visit the LIM Magazine.

Sign up to get these emails in your inbox and never miss a week again!