This Week in Native American News (3/8/19): Amazing Women, Free Pet Services, and Stolen Artifacts

March 8, 2019

REDress exhibit highlights epidemic of missing and murdered indigenous women

The REDress Project, an outdoor art installation by Métis artist Jaime Black at Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington DC. Photograph: Katherine Fogden/National Museum of the American Indian

Thirty-five red dresses hung on winter-bare trees lining the Riverwalk along the National Museum of the American Indian. A woman pushing a stroller stopped to watch the garments twist in the wind, staring at the smallest dress in the collection – one that would fit a little girl.

The REDress Project is a haunting outdoor art installation in Washington DC by Canadian artist Jaime Black meant to symbolize the epidemic of violence against indigenous women and girls.

“Every visitor will have a different experience with the dresses,” said Machel Monenerkit, the deputy director of the National Museum of American Indian. “But you cannot walk through this installation and not have some emotional experience.”

For years and at astonishing rates, Native women in the United States, Canada and across the continent have gone missing or been murdered. Native American women are 10 times more likely to be murdered and four times more likely to be sexually assaulted than the national average, according to a recent report by the US Commission on Civil Rights.

But in the era of #MeToo and after the first two Native American women were elected to Congress in 2018, there is a renewed effort to account for the disappearances and prevent future tragedies.

Read the Full Story Here

In Other Women’s News (on this International Women’s Day)…

HAALAND, DAVIDS INTRODUCE HISTORIC RESOLUTION RECOGNIZING NATIVE AMERICAN WOMEN FOR WOMEN’S HISTORY MONTH

The resolution honors the heritage, culture, and contributions of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian women in the United States. It also calls attention to the challenges that disproportionately affect women in Native communities including the wage gap disparity and domestic violence that contribute to the epidemic of missing and murdered indigenous women.

‘Like Seeing a Piece of Your Heart’: A profile of Lily Tuzroyluke

By the time Lily Tuzroyluke was in college, she’d already shown a drive for community leadership. She interned at Alaska Native organizations as she pursued a degree in justice, organized social welfare programs, and returned to her community of Point Hope to work for the tribal government. Tuzroyluke was meeting with her mentors, Rex Tuzroyluke and Jakie Koonuk, when Rex made a suggestion — couched in a classically Iñupiaq indirect observation. Rex said that over his lifetime he had met a lot of authors, historians and researchers, some big names you’d recognize, who had written about Point Hope. But — and Rex paused — none of them were from Point Hope.

Minnesota veterinary students offer free services to Native American nations

Image by 12019 on Pixabay

From the Inuit Qimmiq to the Salish Wool dog, the Aztec Tlalchichi to the Tahltan Bear dog, canines have long been a staple of Native American cultures. Used for hunting, herding, retrieving, transportation, guarding and companionship, it is likely that both domesticated dogs and wild wolves followed humans as they migrated across the Bering land bridge.

Today, dogs, cats and pets of all stripes are important part of life for many Native Americans. But critical medical care for animals can be costly or inaccessible, forcing pet owners, to at times, make difficult decisions in how they allocate resources.

To ameliorate such situations, students at the University of Minnesota’s College of Veterinary Medicine have offer free clinical service for the animals belonging to individuals living on Native American reservations across the state. Since 2009, Student Initiative for Reservation Veterinary Services (SIRVS) has provided comprehensive coverage, from routine checkups to small surgeries, at its pro bono, pop-up community clinics held on reservations such as those of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe and the White Earth Nation.

Read the Full Story Here

The F.B.I. Is Trying to Return Thousands of Stolen Artifacts, Including Native American Burial Remains

Artifacts on display at Don Miller's farm in 2014. For more than seven decades, Miller unearthed cultural artifacts from North America, South America, Asia, the Caribbean, and in Indo-Pacific regions such as Papua New Guinea. (FBI)

Five years ago, F.B.I. agents descended on a house in rural Indiana packed with ancient artifacts unlawfully obtained by the home’s owner, 91-year-old Don Miller. Over a six-day raid, the agency seized more than 7,000 objects in a collection that ranged in the tens of thousands. It remains the largest single recovery of cultural property in the agency’s history. Witnessing the sheer number of artifacts accumulated was “jaw-dropping,” F.B.I. Agent Tim Carpenter later recollected in an interview with CBC’s Susan Bonner. Most staggering of all was the discovery that Miller had amassed approximately 500 sets of human remains, many of which are believed to have been looted from Native American burial grounds.

Since the raid, the F.B.I. has been quietly working to repatriate the objects and remains to their rightful owners. But to date, only around 15 percent of the horde has been returned. In the hopes of speeding up the identification and repatriation process, the F.B.I. is now publicizing the case.

Read the Full Story Here

Today’s History Lesson

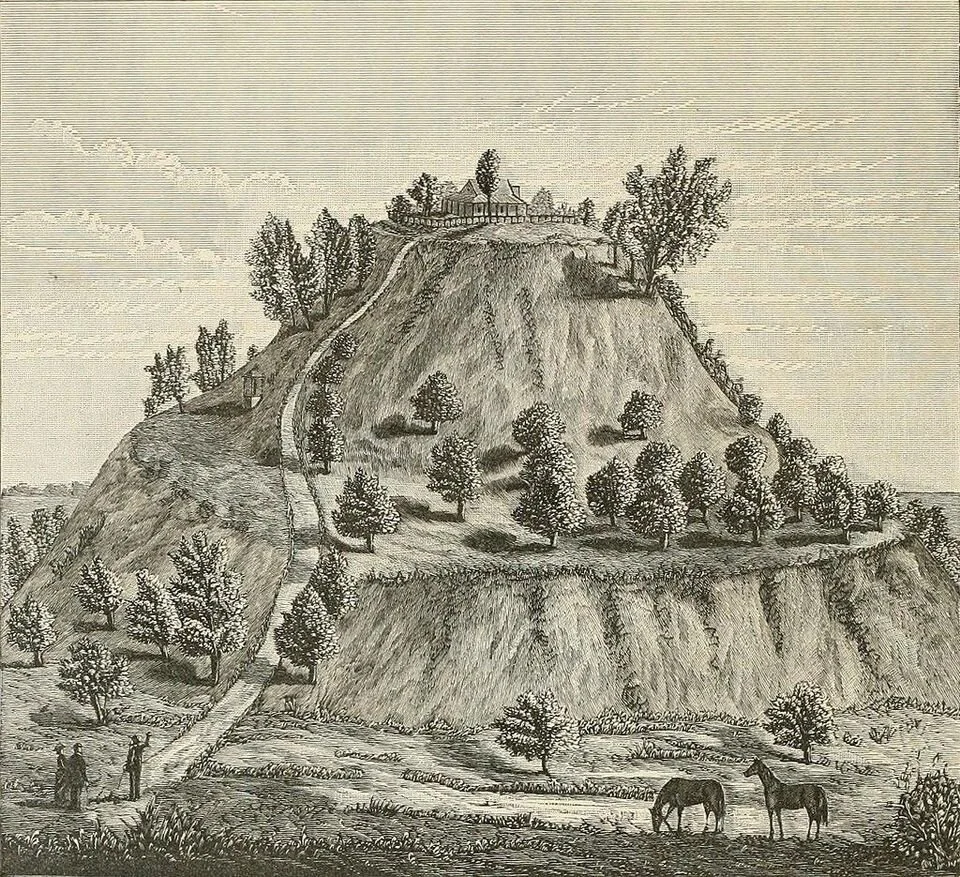

Human Poop Reveals The Fall Of Cahokia

The researchers collected sediment from the bottom of Horseshoe Lake, which lies north of the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site. They were able to obtain both archaeological and environmental data within the samples, permitting them to assess how the size of Cahokia's populations fluctuated with changes in precipitation patterns. Within these samples, they found traces of Cahokian poop in the form of "fecal stanols", molecules that the stomach produces during digestion that are voided along with human feces. Precipitation events likely carried the stanols from land to Horseshoe Lake. And, when Cahokia was more densely populated, more stanols accumulated in lake sediments.

The Schools That Tried—But Failed—to Make Native Americans Obsolete

The Civilization Fund Act of 1819, passed 200 years ago this week, had the purported goal of infusing the country’s indigenous people with “good moral character” and vocational skills. The law tasked Christian missions and the federal government with teaching young indigenous Americans subjects ranging from reading to math, eventually leading to a network of boarding schools designed to carry out this charge. The act was, in effect, an effort to stamp out America’s original cultural identity and replace it with one that Europeans had, not long before, imported to the continent. Over time, countless Native American children were taken from their families and homelands and placed in faraway boarding schools, a process that was often traumatic and degrading.

It's hard to fit so much news in such a small space.

To read all of this week's news, visit the LIM Magazine.

Sign up to get these emails in your inbox and never miss a week again!