This Week in Native American News (5/3/19): Cancer "Angels," the Savannah Act, Alaska Native Poets, and an Amazing Version of the Beatles' "Blackbird"

May 3, 2019

Native American ‘Angels’ Help Ease Burden of Cancer

Photo shows a patient at the Phoenix Indian Medical Center (PIMC) preparing for a mammogram. Facebook/Indian Health Service/PIMC

Cathy Ute knew something was wrong.

“I couldn’t eat and I hurt all over,” said Ute, a member of the Eastern Shoshone tribe from the Wind River Indian Reservation in Fort Washakie, Wyoming. “I was so tired all the time.”

Between 2014 and 2016, Ute made 22 visits to the Indian Health Service's Fort Washakie Health Center, one of two clinics serving a reservation population of nearly 11,000. Each time, her doctor diagnosed her with acid reflux.

“And he would give me these little antacid tablets and say, ‘It’s probably just stress,’” Ute said.

Her doctor finally scheduled her for a computed tomography (CT) scan.

“And then he called and said, ‘You’ve got a big mass in your uterus,’” she said, adding, “And I didn’t even know what a mass was.”

Linda Burhansstipanov, a member of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, is the founder and director of Native American Cancer Research (NACR), a community-based nonprofit in Pine, Colorado, that works to reduce cancer incidence and increase survival among American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/ANs).

She said Ute’s story isn’t surprising.

“This is unfortunately the norm in many areas of Indian Country.”

Read the Full Story Here

A Native American woman's brutal murder could lead to a life-saving law

Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind’s boyfriend Ashston Matheny holds their daughter, as victim impact statements are read during the sentencing of Brooke Crews. Photograph: David Samson/AP

There was heartbreak across Indian country in August 2017 when the body of 22-year-old Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind was found duct-taped in plastic in the Red River.

The ribbon of water demarcates North Dakota from Minnesota, a tributary flowing northward across the Canadian border. It is where, a few years earlier, an indigenous girl, 15-year-old Tina Fontaine, was discovered wrapped in a duvet cover and weighted down by rocks.

The tales of these two tragedies and the river itself are emblematic of a modern violence against one of the world’s most vulnerable populations, indigenous women and girls. It is a problem police and authorities in the US have been accused of ignoring.

Dave Flute is the chairman of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate Nation and leads the United Tribes of North Dakota, a leadership coalition representative of the state’s five-federally recognized tribal nations.

“During the gatherings and prayers for Savanna, we heard story after story from families who also have women in their families missing or with unsolved murders,” said Flute in a letter addressed to North Dakota’s congressional delegation in the weeks following LaFontaine-Greywind’s death. “The murder of Savanna illustrates a much larger problem of epic proportions.”

In the letter sent on behalf of the tribes, leaders outlined 10-points of action for lawmakers to consider. Today, it serves as an aspirational checklist to gauge progress on the violence faced by indigenous women and girls.

Heidi Heitkamp, the former senator of North Dakota, wasted little time responding to the checklist.

“For too long, the disproportionate incidences of violence against Native women have gone unnoticed, unreported or underreported and it’s time to address this issue head on,” said Heitkamp on the day she introduced Savanna’s Act on the Senate floor in Washington DC, just six weeks after LaFontaine-Greywind’s body was pulled from the Red River.

Read the Full Story Here

Why Aren’t We Talking About Indigenous Food?

PHOTO BY MARK WEINBERG

Why aren’t we talking about Indigenous food? The answer to this question will vary depending on whom you ask.

“Well, are you talking about pre-colonial, post-colonial, American Indian, Native American, or today?” poses M. Karlos Baca (Tewa/Diné/Nuche), an Indigenous foods activist. “And where? Spanish, Mexican, or Protestant-colonized from the east?”

David Rico, of the Choctaw Nation and a line cook at José Andrés’ America Eats Tavern, presses further, “What even is Indigenous cooking? The techniques? Ingredients? Cooking off the land solely, using whatever it gives you? Or can you use non-pre-colonial ingredients as well? Are you responsible for removing invasive species? It all depends on your concept of [Indigenous] identity.”

Because Rico’s elders were forcibly removed from their lands again and again, there were no lasting memories, lessons, or relationships with one home or place to pass down. “It feels like we’re just now waking up, looking around and asking: What just happened? What even is ours, and what was imposed upon us?”

Read the Full Story Here

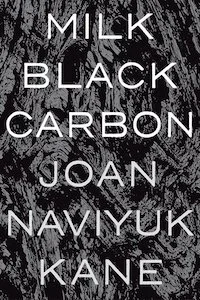

3 ALASKA NATIVE POETS FOR YOU TO READ ASAP

Athabascan girl in Fairbanks, Alaska

LAURA OJEDA MELCHOR writes:

I know I live on stolen land. My house in Alaska is built on originally Indigenous land. To me, it’s good to keep this knowledge in my heart and mind. It’s even better to find out exactly which Alaska Native nation calls my area home and to spend time getting to know the people and their culture and history, which is inevitably and often painfully linked to ours.

So, I now know that the Dena’ina Athabascans originally lived where my neighborhood now sits. There’s a Native-owned primary care center just a few miles from my house. Once my son is old enough, I plan to take him to Native-run events that are open to the public.

Recently I’ve discovered another great way to listen to Alaska Native voices: books. Not books about Alaska Natives, but books they wrote. #OwnVoices books.

In the last month I read three different volumes of poetry by Alaska Native authors, and they each blew me away. Here are three Alaska Native poets for you to read ASAP because they’re just that amazing.

Read the Full Story Here - THEN - Buy the Books:

Listen to This: Student Emma Stevens Covers 'Blackbird' By The Beatles In Mi'kmaq

It's hard to fit so much news in such a small space.

To read all of this week's news, visit the LIM Magazine.

Sign up to get these emails in your inbox and never miss a week again!