This Week in Native American News (4/27/18): Cleaning Indoor Air, Reaching 20-Somethings, and Being Nice (Because It's the Law)

April 27, 2018

Great People Doing Great Things: Professor Works with Navajo Nation to Reduce Indoor Air Pollution

Prof. Lupita Montoya has been working on the Navajo Project, which aims to replace home heating stoves that potentially cause harmful indoor air pollution in Navajo Nation houses. The Navajo Nation is the largest sovereign Native American nation in the United States.

Many of the Navajo people burn a combination of wood and coal in their homestoves, combustion that produces a mixture of harmful emissions such as fine and ultrafine particulate matter (PM), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and carbon monoxide (CO).

In Shiprock, New Mexico, the largest city in the Navajo Nation, higher rates of hospitalization due to respiratory conditions are observed during the winter, when homes are being heated, than during the summer. A study of Navajo homes in and near Ft. Defiance, Arizona showed that, among Navajo children under two years old, wood stove use was associated with increased prevalence of acute lower respiratory infection.

In confronting the task of providing a stove replacement, Prof. Montoya and her colleagues utilized a community-science-based approach, meaning they heavily relied on community input and engagement.

The daily lives of the Navajo people are strongly influenced by their culture and traditions, and thus proposing heating alternatives that both reduced negative environmental and health effects and respected the Navajo culture was crucial.

Wood fire is the traditional Navajo method of home heating and is widely accepted by the Navajo people. Wood pellet stoves, however, require electricity, and the Navajo people may view such a reliance on electricity dangerous to one’s well-being. Essential to understanding such cultural perceptions were a group of Navajo students at Dine College who worked with and were advised by Prof. Montoya. Ultimately, a perception, cultural, and technical assessment framework was adopted to evaluate heating alternatives deemed viable by Navajo stakeholders.

Read the full story here

In Hawaii, Being Nice is the Law

There may be many words to explain the encounters of kindness you experience in Hawaii, but at least one of them is ‘Aloha’. And as it turns out, ‘Aloha’ is actually the law here.

Hawaii now hosts almost nine million visitors a year, and ‘Aloha’ is a word that most of those tourists will hear during their time on the islands. The word is used in place of hello and goodbye, but it means much more than that. It’s also a shorthand for the spirit of the islands – the people and the land – and what makes this place so unique.

“Alo means ‘face to face’ and Ha means ‘breath of life’,” according to Davianna Pōmaikaʻi McGregor, a Hawaii historian and founding member of the Department of Ethnic Studies at the University of Hawaii, Manoa. But McGregor also noted that there are several less literal, but equally valid, interpretations of the word.

Read the Full Story Here

Training Aims To Ease Pain Of Native American Historical Trauma

Native American students, faculty, and staff at the University of Wyoming in Laramie recently participated in a wellness training. The idea was to explore how to process trauma left behind by a dark history.

Native Wellness Institute Trainer Robert Johnston is a member of the Muskogee Creek Tribe and said generations of suppressed language and culture, genocide and boarding schools have left intergenerational scars that manifest in people’s lives as negative behaviors like addiction, depression, illness, and abuse.

Johnston said many tribes have embraced the sobriety movement, but now it’s time to embrace a new movement.

“The wellness movement was about utilizing culture as a way of healing and moving forward from the impacts of historical and intergenerational trauma,” he said. “Across the nation, you saw more efforts to bring to light how can we use our teachings of our ancestors, how can we use our culture?”

Program Coordinator Jordan Cocker is a member of the Kiowa Tribe and a founding member of the “Indigenous 20-Something Project,” an effort to heal the millennial generation of Native youth.

Read the Full Story Here

Your Weekly History Lesson:

The discovery of a map made by a Native American is reshaping thinking about the Lewis & Clark expedition

An important historical map drawn by a Native American leader for renowned American expedition leaders Meriwether Lewis and William Clark was recently discovered in the Bibliotheque Nationale de France.

“Monumental doesn’t fully cover the importance of this discovery,” says historian Clay Jenkinson. “This is easily the best-preserved of the Native American maps drawn for Lewis and Clark, and represents the most important discovery in the Lewis and Clark world since 55 letters by William Clark were discovered in a Louisville attic in the 1980s.”

The Catawba Indian Nation carries on 4,000 year old traditions in S.C.

Before the United States, before the Carolinas, before the Americas, thousands of years before our European and African ancestors landed, willingly and not, on the shores of this vast country, there was a woman kneeling on the bank of the Catawba River. She would have been wrist-deep in the riverbank's thick pan clay, collecting source material to fire into the Catawba tribe's signature pottery. The Catawba were farmers, and the woman would pass rows of corn and squash, perhaps, on her way home.

"I consider myself very fortunate," says Harris of his deep-seated knowledge of Catawba pottery making. "[My grandmother] Georgia Harris was an excellent potter and teacher. She gave freely of the art form and with that I fell in love with it myself at a young age." Harris' grandmother received the 1994 National Endowment for the Arts award for her pottery and, in 2016, Harris himself received the Jean Laney Harris Folk Heritage Award, presented by the S.C. General Assembly.

"I am putting my hands in clay and having that experience knowing I have over 4,000 years of clay making [behind me] and there hasn't been a generational stop in that period ... we are digging clay out of the same clayholes," says Harris.

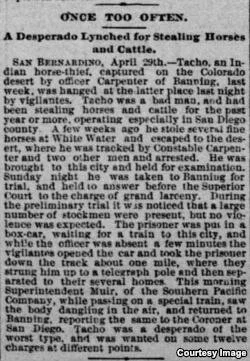

Remembering Native Lynching Victims

This week, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, opens to the public, paying tribute to thousands of African Americans who were lynched by white mobs from the close of the 19th century Civil War through the 1960s. While lynching is most commonly associated with blacks in the southern United States, little attention has been paid to the lynching of other minorities, among them, Native Americans.

In his 2011 book, the Roots of Rough Justice: Origins of American Lynching, Michael J. Pfeifer, history professor at the City University of New York’s (CUNY) John Jay College of Criminal Justice, describes lynching as “informal group murder.”

“The definition that I and many scholars have used stipulates that there has to be an illegally-obtained death perpetrated by a mob -- three or more persons -- and that the collected killing must be in service to justice, race or tradition,” he said.

Watch this: New Documentary Chronicles Indigenous Activist History

It's hard to fit so much news in such a small space.

To read all of this week's news, visit the LIM Magazine.

Sign up to get these emails in your inbox and never miss a week again!