This Week in Native American News (6/1/18): Correcting inaccurate narratives, celebrating Hawaii, and admiring Indigenous designs

June 1, 2018

Native American Photographers Unite to Challenge Inaccurate Narratives

Thousands of veterans and supporters gathered near the Oceti Sakowin Camp for the veterans march in December 2016.CreditTailyr Irvine

When Tailyr Irvine was at the Standing Rock prayer camp in North Dakota she noticed that many of the other photographers there — who had come to photograph protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline — were concentrating on people on horseback or those wearing headdresses. While many of the photographers were well meaning, she said, they relied on overly dramatic visual clichés that gave a distorted view of nativepeople like her.

“Our traditions are important to me,” she said. “But I’m also authentically Indian when I’m just wearing sweatpants.”

Ms. Irvine is a member of the Salish and Kootenai tribes who was born and raised on the Flathead Reservation in northwest Montana. While her family followed native traditions, she rarely saw meaningful stories on Native Americans. The photos she saw were usually based on stereotypes that she calls the four D’s — drumming, dancing, drinking and death.

“You have to go beyond these stories,” Ms. Irvine, 24, said. “They are not, by themselves, an accurate representation of who we are.”

Read the Full Story Here

How three generations of Alaska Natives struggled with cultural education

Gambell, Alaska, is on St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Sea. On clear days, Siberia is visible in the distance. People have lived on the island for thousands of years and developed subsistence hunting strategies and traditions that are still being passed down. (Photo by Kiliii Yuyan for NPR)

On Aug. 24, 1952, the Silook and Oozevaseuk families of Gambell, Alaska, welcomed a baby girl into the world and introduced her to the island that had been their home for centuries.

Gambell is at the western edge of St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Sea. When the weather is clear, you can see Siberia in the distance.

Baby Constance was born into a culture that was rich and well-adapted to the exceptionally harsh environment. Her ancestors had passed down skills for surviving — ways of reading the ice to know when walruses, seals and whales could be caught and methods of fishing in the cold water. Families worked together; subsistence hunting does not favor the greedy. Most people spoke the Alaska Native language, Yupik, with Russian and English words mixed in. That is the language Constance’s mother, Estelle, taught her daughter.

But things were changing. Earlier in the century, missionaries had made it to the island, and World War II had brought soldiers to a base near the village. The distance between the people of Gambell and the federal government was diminishing, and as it did, a wave of cultural destruction that had already torn through American Indian communities across the U.S. and mainland Alaska was bearing down on the community. It would hit Gambell’s children the hardest.

Read the Full Story Here

Land, Loss And Love: The Toll Of Westernization On Native Hawaiians

Hawaiian beach. ART WAGER VIA GETTY IMAGES

Native Hawaiians have a sacred relationship with their land ― a cultural value known as aloha ʻāina, which translates to a love of the land or that which nourishes you ― but centuries of colonization and shady moves by American entrepreneurs have led to the displacement of many natives, according to Kalani Young, a Native Hawaiian researcher currently studying at the University of Washington.

“What it means to be Native Hawaiian [today] is obviously shaped by colonialism and imperialism in Hawaii, so we as a people have a lot of burden to carry and are often blamed for individual failures [like homelessness] that are beyond our control,” Young said.

Young says that Native Hawaiians are especially vulnerable in Hawaii’s current cost-of-living and affordable housing crises because the current system, installed by the U.S. after Hawaii was annexed and statehood was established, was designed to benefit “non-Hawaiians who are not from here and who have access to resources that [Hawaiians] don’t have.”

Read the Full Story Here

You might also be interested in...

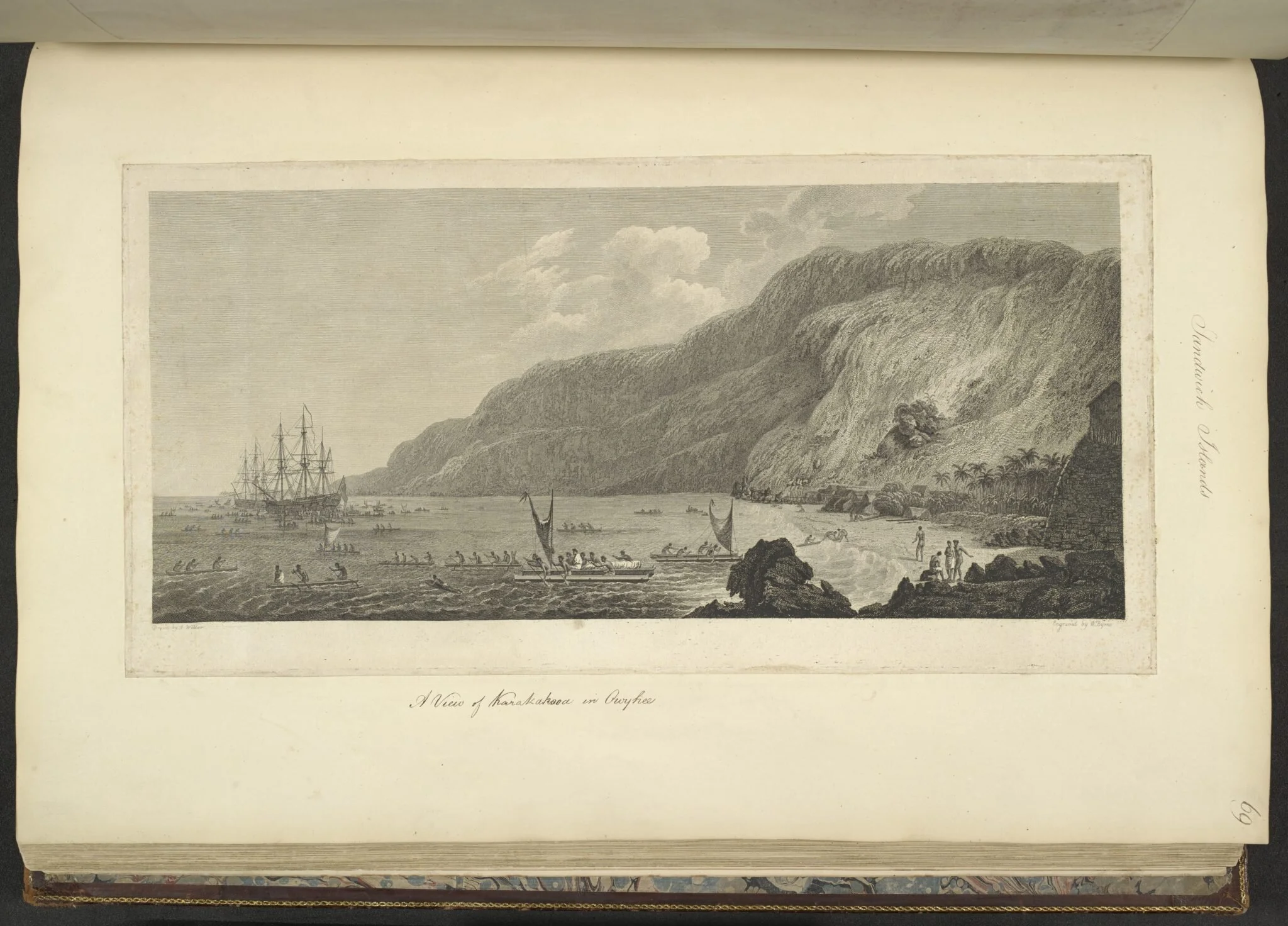

“View of Karakakooa in Owhyhee,” drawn by John Webber and engraved by W. Byrne. The drawing is part of the “James Cook: The Voyages” exhibit at The British Library in London.

How The World Is Celebrating Hawaii This Year

The cultural treasures of ancient Hawaii were scattered to the four winds during the six decades after the Europeans and Americans first arrived in the islands.

Hundreds of sacred items of enormous value — including feathered cloaks, capes, carved figures and statues of gods — were given away, traded for goods from overseas or simply stolen by foreigners.

“This is an interesting year to write about these things,” said Noelle M. K. Y. Kahanu, an assistant specialist in Native Hawaiian programs at the University of Hawaii and one of the leading experts on Hawaii’s precious patrimony.

This year is the 250th anniversary of Captain Cook embarking on his voyages of discovery, she said, adding that many institutions have prepared special shows to highlight items in their Pacific collections.

How 6 Indigenous Designers Are Using Fashion to Reclaim Their Culture

Keri Ataumbi Label: Ataumbi Metals Tribe: Kiowa Based in: Santa Fe, New Mexico

The line between inspiration and appropriation in fashion is oftentimes blurred. Nobody knows this better than the indigenous community, whose sacred prints, hand-burnished leatherwork, and beaded appliqués have been imitated by fashion houses for centuries. This type of cultural appropriation, where labels draw from deep-rooted design codes without crediting the culture they are taking them from, is particularly harmful to indigenous people, who have been, and continue to be, marginalized. But now, a new crop of indigenous designers in North America is fighting back, using their collections to spotlight cultural activism and grassroots movements that are more important now than ever.

These unique designers hail from a variety of distinctive tribes, from Ojibwe to Kiowa, and are fusing their cultures’ time-honored craftsmanship with new, unexpected flourishes, such as graphic silk screen or 3-D printing. The unifying message? Reclaiming their heritage in a time when indigenous people continue to remain invisible. The collections, which range from jewelry to ready-to-wear, find inspiration in traditionally meaningful elements such as animals, historical government documents, and ornate regalia pieces, such as the powwow dresses worn by Crees, Crows, and many other groups, each one different in nature. “The biggest misconception about indigenous design is that it’s all the same,” said designer Bethany Yellowtail. “Crows are very different than Navajos, and Cheyennes are very different than Ojibwes. It’s really important to tell those stories through our design.”

Read the Full Story and See the Designers Here

Your Weekly History Lesson:

Pipeline "man camp" (Jon Lowenstein/NOOR/REDUX)

Historical Colorized Pictures Show Native Americans at the White House for Citizenship in the 1920s

These incredible photographs were colorized by British colorization specialist Royston Leonard. The remarkable pictures show the group during the 1920s, with some of the leaders meeting with then American president, Calvin Coolidge, at the White House.

In 1924, the Indian Citizenship Act was proposed by Representative Homer P. Snyder and signed by President Calvin Coolidge, meaning the indigenous peoples including the Native American tribe, also known as Native Indians, were granted full U.S. citizenship.

This Ancient Rock Art Does Something Incredible Every Summer Solstice

It was only until relatively recently that locals noticed a curious feature on the largest and best-preserved petroglyph site in the valley, the V-Bar-V Heritage Site.

On the summer solstice, the shadows cast by the two rocks fall down on a petroglyph below, perfectly framing the carvings of a corn plant and a dancing figure with the Sun’s beam. The fact this precise light show only occurs around the year’s longest day is no coincidence.

It's hard to fit so much news in such a small space.

To read all of this week's news, visit the LIM Magazine.

Sign up to get these emails in your inbox and never miss a week again!