This Week in Native American News (6/7/19): Remembering D-Day, Returning to Traditional Birthing Practices, and Honoring Female Artists

June 7, 2019

On the 75th Anniversary of D-Day, Native Americans Remember Veterans’ Service and Sacrifices

Command Sergeant Major Julia Kelly (U.S. Army retired), one of 80 Native American delegates to the 75th anniversary observance of D-Day, stands on Omaha Beach. Kelly holds an eagle feather staff, an American Indian symbol of respect, honor, and patriotism. (Courtesy of Julia Kelly)

Eighty Native American delegates have traveled to France to commemorate the 75th anniversary of D-Day. On June 6, 1944, the largest amphibious invasion in history began as Allied forces landed on the Normandy coast. Some 160,000 soldiers, sailors, and airmen, aboard 5,000 ships and 13,000 aircraft, stormed the beaches to establish a foothold for the liberation of Western Europe. Among those troops were American Indians who, like their ancestors, accepted the responsibilities of warriors.

The Native representatives taking part in the commemoration are members of the Charles Norman Shay Delegation, named for a decorated Penobscot Indian veteran of the Normandy invasion. “We are going to support D-Day anniversary activities during ten days of events,” says Command Sergeant Major Julia Kelly, an enrolled citizen of the Crow Tribe and one of five Native women in the delegation representing the United Indigenous Women Veterans. “They will keep us very busy.”

A U.S. Army medic from Indian Island, Maine, Private Shay was attached to one of the first regiments to land on Omaha Beach, the most heavily defended sector of the coast. Shay began treating the wounded as soon as he got his footing, dragging wounded soldiers out of the surf under constant fire. After the war, the U.S. Army awarded Shay a Silver Star for his actions, and the French government appointed him a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur, the highest honor given to noncitizens of France.

Two years ago today, on the 73rd anniversary of D-Day, in a park overlooking Omaha Beach, the people of Normandy dedicated the Charles Shay Memorial. The first French monument to honor American Indian soldiers who fought on D-Day, it is part of a growing movement to acknowledge Native Americans’ contributions during World War II. To Shay, the simple stone turtle that stands as the park’s monument represents all the “Indian soldiers who left Turtle Island to help liberate our allies.”

Read the Full Story Here

How one midwife is helping indigenous mothers connect to their childbirth traditions

Musqueam councillor and former chief Wendy Grant-John says the Women Deliver 2019 Conference offers a chance to learn about lesser-known impacts of European imperialism.

Ms. Kolakowski decided to give birth at home after she passed out at work early in her pregnancy. A coworker rushed her to the hospital, where she was treated for dehydration.

“I didn’t like being confined in bed and had all these IV’s in me,” she said. “I was just like, ‘I hate this.’”

For her prenatal care, she turned to the Santa Fe Indian Hospital; but even that, she said, was nothing like what she felt she would experience under the care of Ms. Gonzales. With her, she felt empowered in a very different way.

“It didn’t feel like something was happening to me,” she said. At the hospital, it was all about the baby. “I mean, that’s important, don’t get me wrong,” she said. “But [becoming a mother] is also a huge transformation.”

And that transformation, for Ms. Gonzales, is a sacred one.

Early in her career, Ms. Gonzales worked for the Indian Health Service as a nurse, then spent a decade working in private hospitals, and eventually earned her master’s degree in nursing midwifery from the University of New Mexico while working. In 2015 she launched the Changing Woman Initiative, envisioning a birthing center for indigenous women. A few years later, she left her job as a midwife to devote all her time to it.

Changing Woman, or Asdzáá Naadleehi, the center’s namesake, is a sacred creator in the Navajo culture who represents, as Ms. Gonzales put it, transformation. Ms. Gonzales’s goal is to offer women the space to bring back ancient tribal birthing practices and, at the same time, provide much-needed care and information to women who might not otherwise be able to get it.

Read the Full Story Here

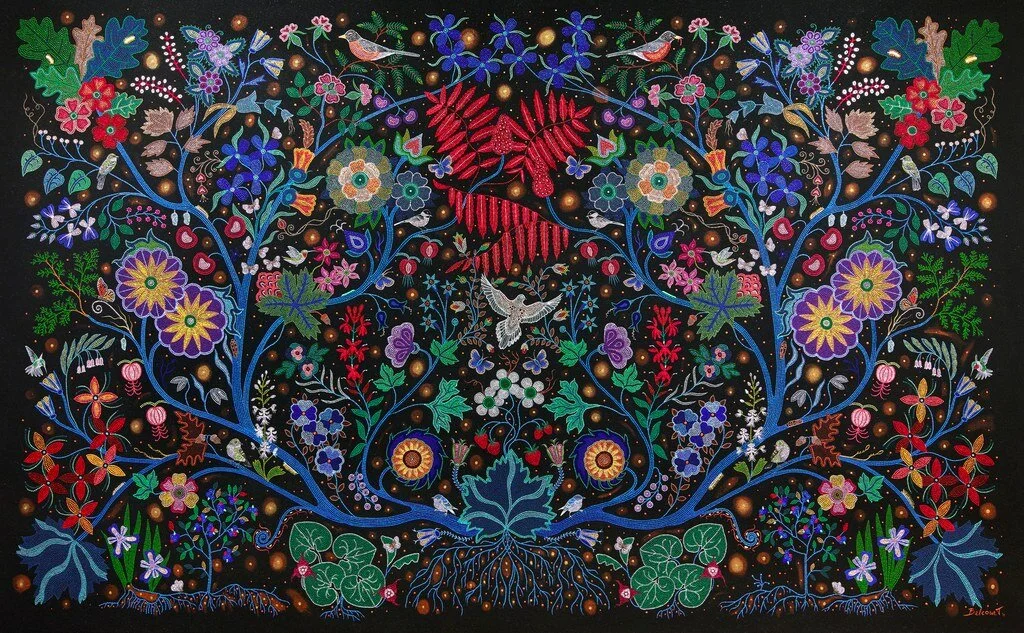

Inside the First Major Museum Exhibition Celebrating Native Women Artists

The Wisdom of the Universe by Christi Belcourt (Michif). Courtesy Minneapolis Institute of Art

When "Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists" opens on June 2 at the Minneapolis Institute of Art in Minnesota, history will be rewritten—and that’s no overstatement.

Ten years in the making, it is the first major museum exhibition to trumpet the artistic achievements of Native women. Its scope is unprecedented: 117 works on display, including paintings, sculpture, textiles, photography, and decorative arts. The pieces span more than a millennium and represent Native women in communities throughout Canada and the U.S.

“If you go into any exhibition of historic Native American art and look around, probably 80 percent of what you’re looking at is women’s work,” says co-organizer Teri Greeves, an independent curator and member of the Kiowa Nation. “But museums never recognize that. There’s no female pronouns in the wall text, no female pronouns in the books. It’s just like ‘the Arapaho’ or ‘the Shoshone.’”

With “Hearts of Our People,” Greeves wants women past and present to stake their rightful claim in the art world. “By finally gendering these historic and contemporary objects, it is my hope that in the future we start talking about the women who made them and recognize that what we understand as ‘iconic Native American art’ was by and large made by women.”

Read the Full Story Here

This Week’s History Lesson…

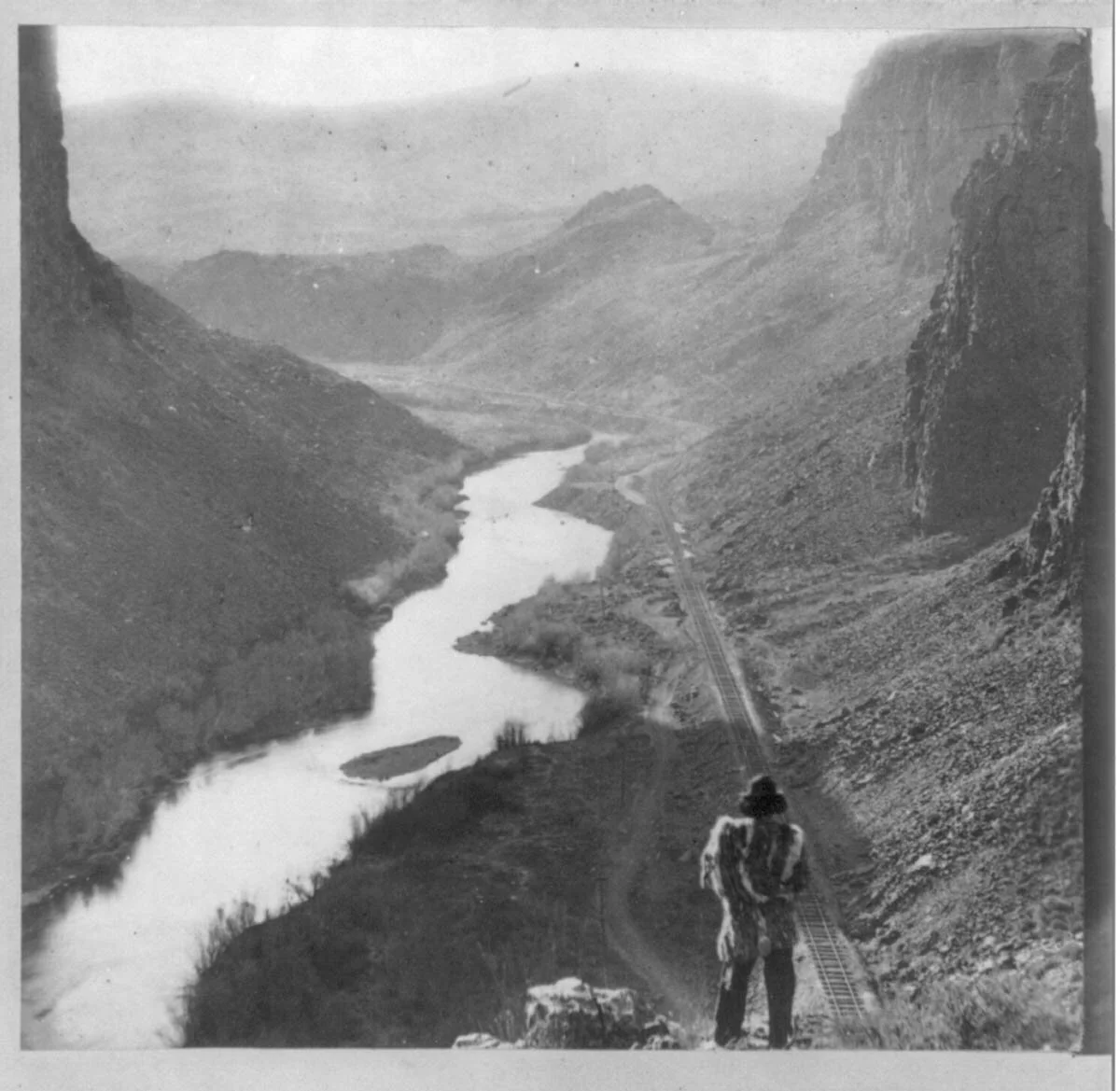

The impact of the Transcontinental Railroad on Native Americans

The Transcontinental Railroad was completed 150 years ago, in 1869. In 1800s America, some saw the railroad as a symbol of modernity and national progress. For others, however, the Transcontinental Railroad undermined the sovereignty of Native nations and threatened to destroy Indigenous communities and their cultures as the railroad expanded into territories inhabited by Native Americans.

I asked Dr. Manu Karuka, American Studies scholar and author of Empire’s Tracks: Indigenous Nations, Chinese Workers, and the Transcontinental Railroad, about the impact of the railroad on Indigenous peoples.

Indigenous people are often present in railroad histories, but they form a kind of colorful backdrop that establishes the scene. Rarely, if ever, do we get an understanding of the interests that drove Indigenous peoples’ actions in relation to the railroad. Rather than analyzing Indigenous peoples’ commitments to their communities and their homelands, railroad histories have emphasized market competition and westward expansion. Focusing on Indigenous histories reveals how Indigenous nations have survived colonialism.

It's hard to fit so much news in such a small space.

To read all of this week's news, visit the LIM Magazine.

Sign up to get these emails in your inbox and never miss a week again!