This Week in Native American News (10/18/19): finding ancestors, seeking land, and then playing a round of golf

October 18, 2019

‘Rez golf’: Where fairways are dirt and hazards include goats

Donald Benally digs the sixth hole on Wagon Trail to Lonesome Pine golf course on the Navajo Nation reservation in Steamboat, Ariz. (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

As golf courses go, Wagon Trail to Lonesome Pine does little to conjure the world of Brooks Koepka or Rory McIlroy. Think manicured Augusta. Think lush Pebble Beach. Then think the exact opposite. This is “rez golf,” a Native American twist on an ancient sport that is swiftly gaining popularity here on the Navajo Nation reservation.

Rez golf, like rez life, is hard — punishing at times. Linger on a brown too long and red ants bite the ankles. Balls are lost forever in spiky sage. The sun is merciless, golf carts absent and booze illegal. An errant goat, sheep or horse can delay play or spoil a shot.

But in an impoverished region where unemployment is over 40%, recreation scarce and drugs and alcohol constant temptations, a few holes and a thrift store club can be a welcome diversion. More than a dozen courses have sprung up on the Navajo Nation. Most holes are just buried tin cans or plastic cups marked by sticks or plastic flags.

Wagon Trail to Lonesome Pine, one the biggest courses on the West Virginia-sized reservation, began 15 years ago with two holes a hundred yards apart.

Read the Full Story Here

What not to wear: Killa Atencio on Indigenous fashion and the line between appropriation and uplifting cultural identity

Killa Atencio is passionate about honouring her culture through art and fashion.

Hailing originally from Listuguj First Nation in Mi’kmaq Territory (Quebec), the young entrepreneur is proud of her Mi’kmaq and Quechua ancestry, and aims to celebrate this heritage through her self-made beaded accessory business, Moonlight Works.

During an interview Wednesday as part of her role as StarMetro Halifax guest editor, Atencio spoke about the central role of fashion in showcasing cultural identity, and the lines between appropriating or uplifting that cultural identity when it comes to the things people wear.

Atencio acknowledges that in an ever-changing and intermingling world, cultural appropriation isn’t going away any time soon. She believes holding each other accountable and learning from mistakes is the path to respecting the ceremonial and traditional power that both art and fashion can hold.

Read the Full Story Here

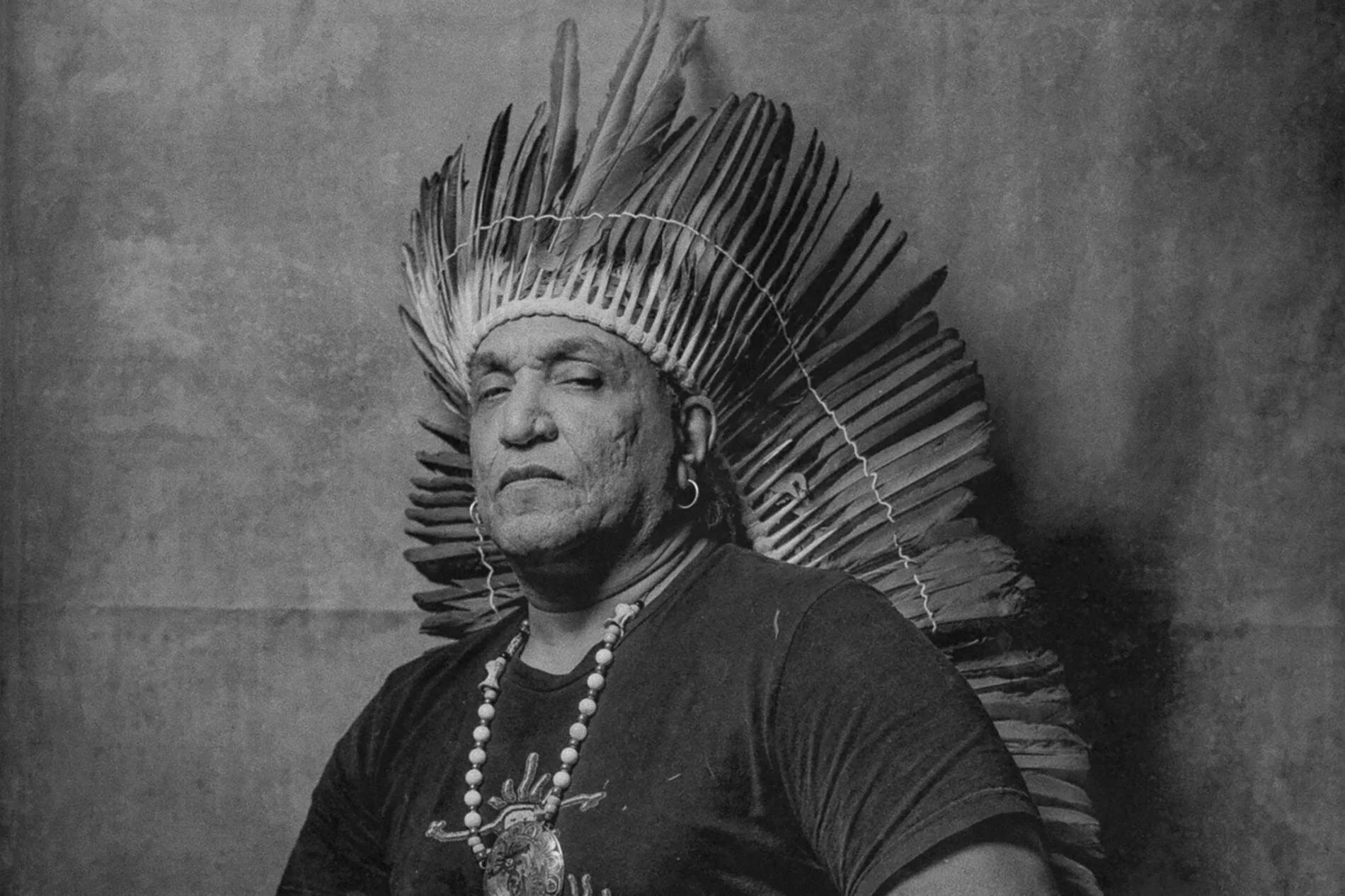

Meet the survivors of a ‘paper genocide’

For centuries, the indigenous people of the Caribbean, known as Taíno, were said to be extinct. But recently, historians and DNA testing have confirmed what many modern, self-identifying Taíno already believed: that a genocide was carried out on paper, after the census stopped counting them, but their identity persisted. Jorge Baracutei Estevez (above), who leads a Taíno community group in New York, worked with photographer Haruka Sakaguchi to depict modern-day Taíno and their reimagined census entries. PHOTOGRAPH BY HARUKA SAKAGUCHI

The people we now call Taíno discovered Christopher Columbus and the Spaniards. He did not discover us, as we were home and they were lost at sea when they landed on our shores. That’s how we look at it—but we go down in history as being discovered. The Taíno are the Arawakan-speaking peoples of the Caribbean who had arrived from South America over the course of 4,000 years. The Spanish had hoped to find gold and exotic spices when they landed in the Caribbean in 1492, but there was little gold and the spices were unfamiliar. Columbus then turned his attention to the next best commodity: the trafficking of slaves.

Due to harsh treatment in the gold mines, sugarcane fields, and unbridled diseases that arrived with the Spanish, the population rapidly declined. This is how the myth of Taíno extinction was born. The Taíno were declared extinct shortly after 1565 when a census shows just 200 Indians living on Hispaniola, now the Dominican Republic and Haiti. The census records and historical accounts are very clear: There were no Indians left in the Caribbean after 1802. So how can we be Taíno?

Read the Full Story Here

‘Landless’ tribes stake out selections in the Tongass

Aerial view of an estuary on Prince of Wales Island in the Tongass National Forest of Southeast Alaska. Photo credit: © Erika Nortemann/TNC

Southeast Alaska tribal communities who were excluded from forming village corporations in the 1970s continue to push for a land settlement. Residents and descendants of natives in Wrangell, Petersburg, Tenakee Springs, Ketchikan and Haines call themselves landless tribes. The effort, backed by Sealaska regional native corporation, has released a series of maps with acreage it’d like sliced out of Tongass National Forest.

A multi-million dollar federal settlement to Tlingit and Haida tribal members over traditional lands lost was one of the largest payouts at the time. The year was 1968 and the case had been going on for decades. The $7.5 million was divided among tens of thousands of tribal members living in Wrangell, Haines, Skagway, Petersburg, Douglas, Juneau and Sitka.

But then came the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act or ANCSA just a few years later. Through this federal legislation, a dozen Southeast communities were able to form village corporations and receive land. But not those compensated through the 1968 case decision.

It wasn’t completely clear cut. A separate provision allowed the more urban communities of Juneau and Sitka to form village corporations. Today there’s Goldbelt and Shee Atika which are thriving.

To the Southeast tribal members excluded by ANSCA, it wasn’t a fair deal.

Read the Full Story Here

It’s hard to fit all the news in a little space.

To read all of this week's news, visit the LIM Magazine.

Sign up to get these emails in your inbox and never miss a week again!